20 March 2020

It is a rare occasion when we discover something completely new to us. In this instance, a discovery of a rare Edward Pugin fireplace surprised us, popping up in Surrey surburbia. Here is a little about the home we believed it was designed for...

For almost a thousand years, Gothic architecture was reserved for Ecclesiastical and scholastic buildings. The style conjured ideas of piety and solemnity, so it was radical to suggest that this architectural style could be used for anything less than a Bishop’s palace or an important seat of learning.

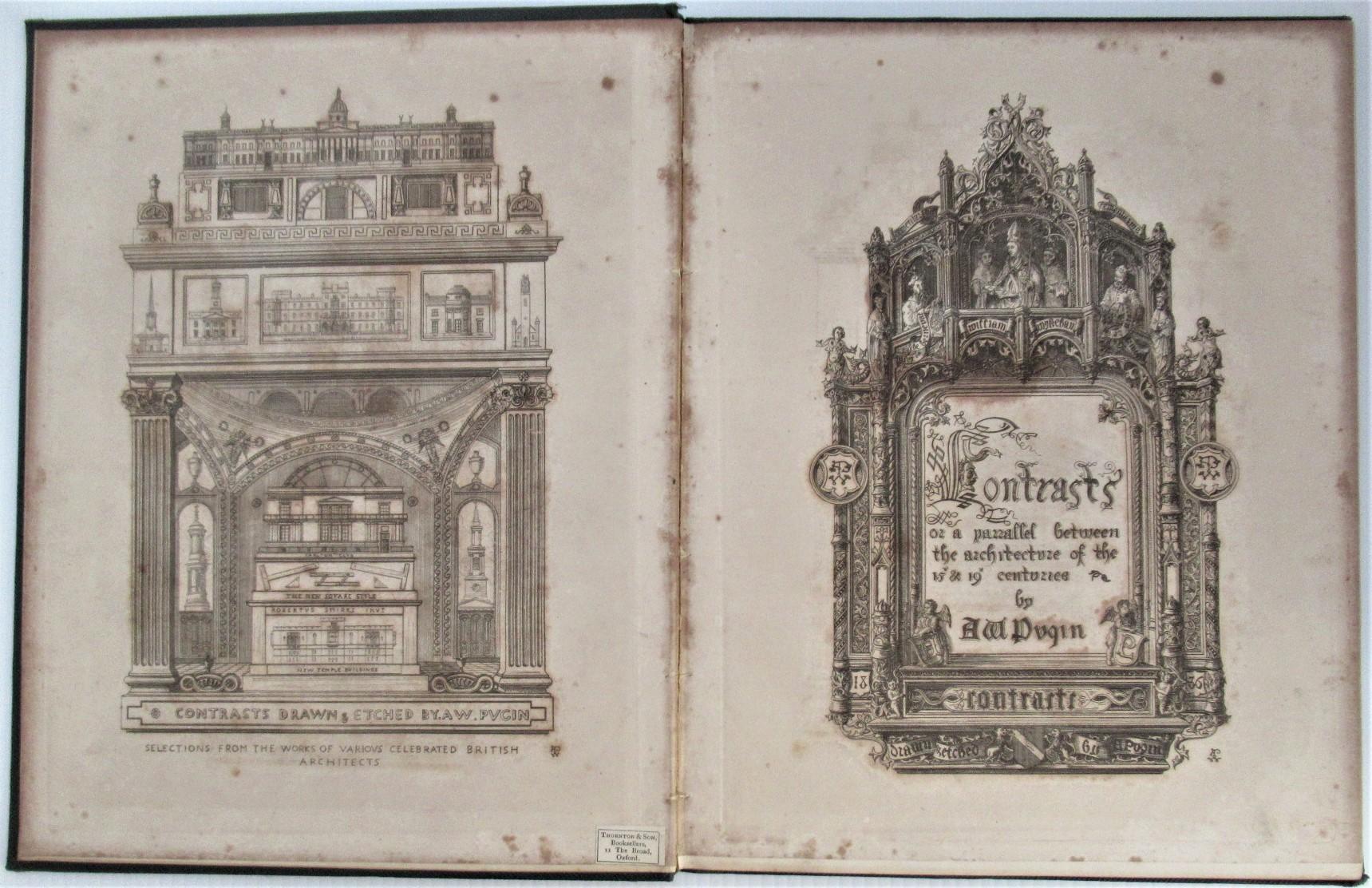

There was no direct historical precedent for domestic Gothic architecture, but one architect set to change this. His name was Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, and he published his architectural manifesto Contrasts in 1836, when he was only 24.

Contrasts argued for a reformed architecture, a medieval revival that would replace what he felt was the stagnant neoclassicism that had spread throughout the country. It was also a return to the church, borrowing the Gothic Style that had existed only in ecclesiastical and monastic spaces before. He reinvented domestic architecture in a way that has now become so normalised that his influence is almost imperceptible.

He believed that form should follow function, a concept that was revolutionary at the time, prioritising the use of the building over its external appearance. This led to an uncontrived asymmetry that proliferated in many buildings to come. After the formal terraces of even the more humble classical dwellings, this shift was radical.

As a result of this manifesto, Pugin was seen as the driving force of the Victorian Gothic Revival, undermining the paganism of classical antiquity and instead imbuing architecture with a sense of medievalism that had been lost somewhere in the Renaissance.

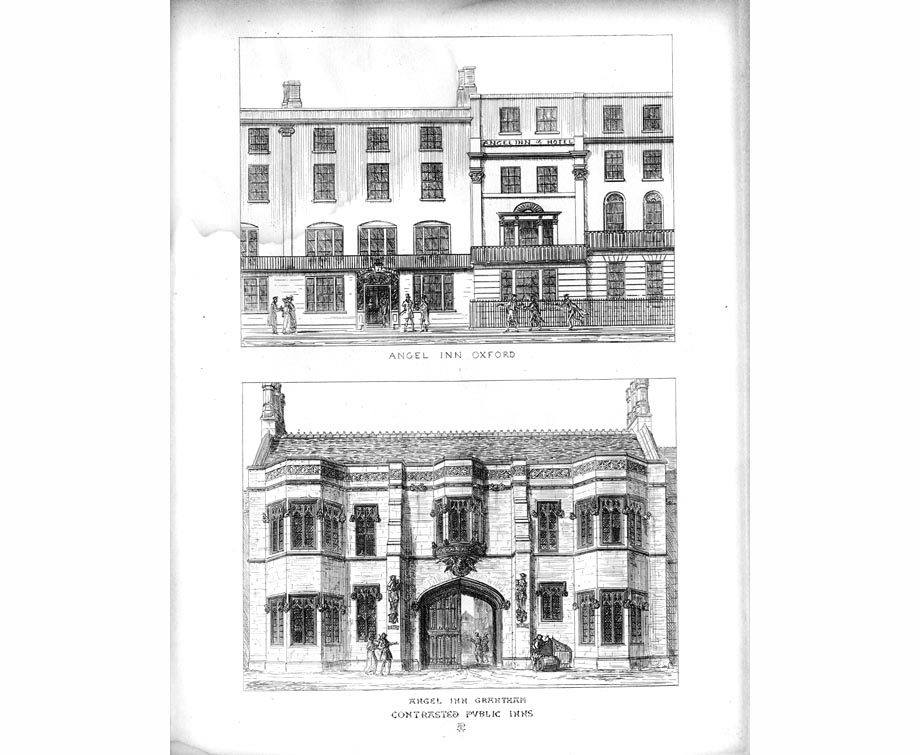

A perhaps unfair comparison illustrated in Pugin's Contrasts. Note the more pleasing composition of his engraving of the Gothic inn juxtaposed against the deliberately unbalanced view of the classical inn situated in a terrace.

Pugin had received no formal education of any kind, and no architectural training, but grew up in a stimulating household in Bloomsbury, where his Anglo-French father A.C. Pugin worked as an architectural draftsman and ran a drawing school with his wife from his top floor studio.

The creative microcosm of Bloomsbury was the perfect environment for the young Pugin to learn the art of architectural design, with his home often hosting John Nash among other eminent architects. Despite his exposure to architects known for their classical principles, he lived in a world where the Renaissance hadn’t happened, a world of flying buttresses, pointed arches and stone tracery. For Pugin, Gothic architecture represented his strong Christian values, rather than the pagan roots of classicism in ancient Greece and Rome.

Of the few domestic buildings he designed, The Grange in Ramsgate was always intended to be Pugin’s final family home. It was relatively simple in design, but incorporated Gothic features designed by him; from the imposing exterior down to the wallpaper. The Grange was built in a pioneering way, as the rooms inside were considered before the façade of the building was conceived. This was in contrast to the Georgian style before it, where the façade was of paramount importance.

The Grange was built in such a way that it prioritised the placement of windows and chimneys based on where they were best suited inside the rooms, not best suited to the façade. A church and monastery were also designed and built on the site and helped Pugin to recreate the medieval social structure he so admired.

The Grange at Ramsgate

The Grange rear facade at Ramsgate

Tragically, Pugin only lived long enough to spend two busy years at the house. It would however remain the family home until 1928 and was altered to accommodate the needs of the large family and the development in style during the Victorian era. His eldest son, Edward Pugin was the last one to make significant structural and decorative changes to The Grange.

Edward was educated at home by his father, working with him from an extremely young age. At only 17, when his father became ill and died shortly after, he assumed responsibility for the home and the architect’s practice. Ten years after Pugin’s death, Edward returned to The Grange to make it his family home once more, living with his stepmother Jane and other members of the family. Now an eminent architect in his own right, Edward made alterations to the house that reflected his own, grander style. Edward did not leave The Grange a shrine to his father, but rather modelled it to his own more High Victorian tastes.

A good example of his more opulent taste is the stone fireplace in his stepmother’s bedroom. It perfectly encapsulates the Gothic Revival style, with a pointed arch surrounded by spandrels of ivy carved in high relief and pilasters in the highly sought-after cippolino marble. The example still situated at Grange Park is also gilded on these carved spandrels, capitals and undershelf.

We have recently tracked down a fireplace almost identical to Edward’s Grange Park fireplace, and it is very likely that it was also made for The Grange. As the home was bequeathed to be run as a school by the monastery next door after the death of Pugin’s youngest son, much of its contents were dispersed at this time. Perhaps this was when the fireplace was sold on, as we discovered it in an early 20th century house in Surrey, for which it was certainly not intended!

Some images of this exciting new find below:

If you would like to know more about this important piece, please do not hesitate to get in touch.