08 August 2017

An essential rite of passage for young gentlemen of means and the final step in the completion of their education, the Grand Tour was an important cultural pilgrimage spanning the 17th and 19th centuries. Seen as the transitional step between boyhood and adulthood, those undertaking the Tour would have left a British Port, often Dover, and set sail for France. Tours were seldom solo journeys; most young men were accompanied by a guide – called a bear-leader – with extensive knowledge of the arts and languages they would encounter. Often the group would extend to doctors and an entourage of servants that guaranteed the level of luxury which the tourist had grown to expect.

These tourists descended on the monuments, sights and galleries of the greatest European cities, first Paris, then Venice, Rome, Athens…

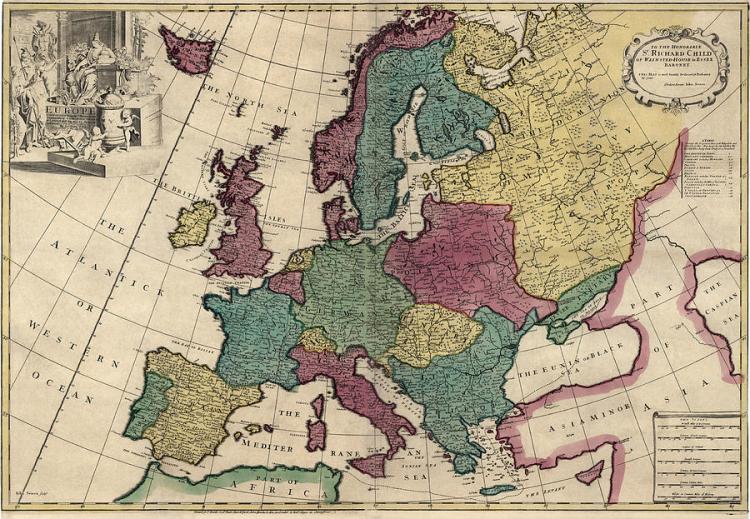

John Senex, Map of Europe. Published London, 1740. Image courtesy of: Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

It was in the 18th century that the tour truly took off, shaping British taste, art and architecture forever. As more and more individuals took part in this cultural phenomenon, the great houses of Britain were reimagined, modelled on the ancient temples and grand European palaces they had visited. These homes and gardens had to be filled, and they were decorated enthusiastically with objects acquired on these tours, some pieces replicas and bespoke items, others relics of antiquity. The Grand Tour later developed in to a buying spree of sorts, the growing taste for European style in Britain sent tourists scouring the continent for objects to fill their homes, reflecting their refinement as a connoisseur of European style.

With the growing popularity of the Grand tour, Britain also saw a taste for Italianate gardens develop.These gardens, studded with sculptures and fountains evoking those of classical antiquity, echoed the tastes of generations who had explored the grandest sights in Europe.

One particularly striking pair of sculptures in our collection is the Rothschild Goats. Carved from Carrara marble, they embody the elegance of Italian sculpture, and echo the flamboyance of the Rococo style which swept through much of Europe in the 18th century.

The Rothschild Goats in our garden.

Standing atop two large plinths, the goats are accompanied by putti. The scene exudes bacchanalian opulence, the putti garlanded and holding bunches of grapes as though on a bacchic procession, to venerate Bacchus, God of wine, fertility and the harvest. Often depicted being ridden by Silenus, a satyr and tutor of Bacchus, and also pulling Bacchus’s chariot, goats symbolised revelry and hedonism. This pair of sculptures embodies this symbolism and brings the classical mythology together with the playfulness of the Rococo style.

The sculptures resided in the grounds of Rushbrooke Hall, a moated manor house in Suffolk. The manor house had 13th century origins and was remodelled in the 18th century, to include formal gardens, the perfect backdrop for marble statuary. Purchased by the Rothschild’s in 1938, it is likely the case that these pieces were purchased specifically for this garden. Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild acquired painting of a remarkably similar scene in the 19th century. Initially attributed to the great 18th century Rococo master, Boucher, this work also depicts a strikingly similar scene…and seemingly an inspiring one!

Allegory of Autumn, after Luigi Soldini, c.1750. (Initially attributed to François Boucher). Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of: National Trust